The euro area crisis, often also referred to as the eurozone crisis, European debt crisis, or European sovereign debt crisis, was a multi-year debt crisis and financial crisis in the European Union (EU) from 2009 until, in Greece, 2018. The eurozone member states of Greece, Portugal, Ireland, and Cyprus were unable to repay or refinance their government debt or to bail out fragile banks under their national supervision and needed assistance from other eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The crisis included the Greek government-debt crisis, the 2008–2014 Spanish financial crisis, the 2010–2014 Portuguese financial crisis, the post-2008 Irish banking crisis and the post-2008 Irish economic downturn, as well as the 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis. The crisis contributed to changes in leadership in Greece, Ireland, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Slovenia, Slovakia, Belgium, and the Netherlands as well as in the United Kingdom. It also led to austerity, increases in unemployment rates to as high as 27% in Greece and Spain, and increases in poverty levels and income inequality in the affected countries.

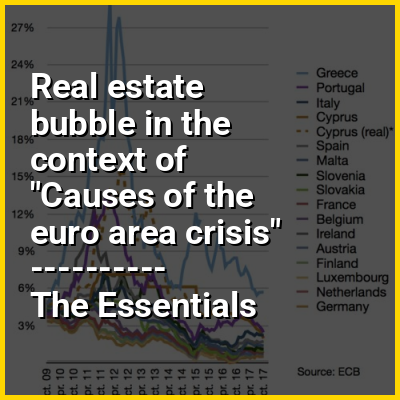

Causes of the euro area crisis included a weak economy of the European Union after the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession, the sudden stop of the flow of foreign capital into countries that had substantial current account deficits and were dependent on foreign lending. The crisis was worsened by the inability of states to resort to devaluation (reductions in the value of the national currency) due to having the euro as a shared currency. Debt accumulation in some eurozone members was in part due to differences in macroeconomics among eurozone member states prior to the adoption of the euro. It also involved a process of cross-border financial contagion. The European Central Bank (ECB) adopted an interest rate that incentivized investors in Northern eurozone members to lend to the South, whereas the South was incentivized to borrow because interest rates were very low. Over time, this led to the accumulation of deficits in the South, primarily by private economic actors. A lack of fiscal policy coordination among eurozone member states contributed to imbalanced capital flows in the eurozone, while a lack of financial regulatory centralization or harmonization among eurozone member states, coupled with a lack of credible commitments to provide bailouts to banks, incentivized risky financial transactions by banks. The detailed causes of the crisis varied from country to country. In several EU countries, private debts arising from real-estate bubbles were transferred to sovereign debt as a result of banking system bailouts and government responses to slowing economies post-bubble. European banks own a significant amount of sovereign debt, such that concerns regarding the solvency of banking systems or sovereigns are negatively reinforcing.